The Canadian Poultry Research Council manages research under four interlinked categories to address issues from all stakeholders

Text by Nicolas Heffernan

Think of Canada’s poultry cluster as a big wheel. The spokes are different research projects, funding mechanisms and communication channels that reach out to industry, academia and government. But at the centre of it all is the Canadian Poultry Research Council (CPRC).

Think of Canada’s poultry cluster as a big wheel. The spokes are different research projects, funding mechanisms and communication channels that reach out to industry, academia and government. But at the centre of it all is the Canadian Poultry Research Council (CPRC).

“The CPRC acts as the hub of the wheel, but we have funding from something like 22 different industry organizations,” says Bruce Roberts, CPRC’s Executive Director. “It’s mindboggling. There are about 35 to 50 organizations that are somehow feeding information into us about what’s important to them for research from the producers’ side. Then we have regular discussions with other companies like food companies, vet and medical organizations and breeder companies. And the universities also have direct contact with those same types of organizations and corporations.”

This cluster is the second iteration of an original cluster which started with Growing Forward. Growing Forward Two allowed the CPRC to continue some projects, while gaining more funding and the ability to launch more projects that will last longer. The cluster gets three government dollars for every industry dollar. The poultry cluster is also a little bit different than others because the CPRC represents four national production organizations and one processing organization (Chicken Farmers of Canada, Canadian Hatching Egg Producers, Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council, Egg Farmers of Canada and Turkey Farmers of Canada), which support the cluster’s research activities. “It gives us a different focus to a certain extent, makes it a little more challenging to address all of the allotted research concerns and requirements of our organizations,” says Roberts. “The cluster, because of its size and dollar values that we’re able to bring together, has already allowed us to address a lot of issues in research.”

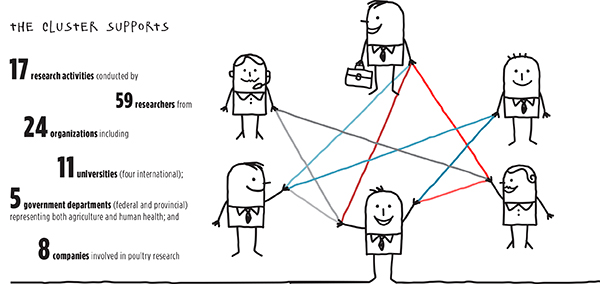

Indeed, the cluster supports 17 research activities conducted by 59 researchers from 24 organizations including 11 universities (four international); five government departments (federal and provincial) representing both agriculture and human health; and eight companies involved in poultry research. This is all done thanks to total funding of almost $5.6 million, including industry contributions of $1.45 million with the balance from government. Each research activity is led by a principal investigator from a Canadian university.

While it might get chaotic at times for Roberts, the research that this web of collaboration permits makes all the headaches worth it. “It allows us to do more than we would normally be able to do just because it’s a program rather than just looking at individual projects,” says Roberts. The cluster is developed under four main categories: poultry infectious diseases, alternative animal health products and management strategies, poultry welfare and well-being and environmental stewardship. “All of them are very much interlinked and address all the major issues we hear about from producers, consumers, government, health authorities,” says Roberts. “We have a lot of research to do.”

While it might get chaotic at times for Roberts, the research that this web of collaboration permits makes all the headaches worth it. “It allows us to do more than we would normally be able to do just because it’s a program rather than just looking at individual projects,” says Roberts. The cluster is developed under four main categories: poultry infectious diseases, alternative animal health products and management strategies, poultry welfare and well-being and environmental stewardship. “All of them are very much interlinked and address all the major issues we hear about from producers, consumers, government, health authorities,” says Roberts. “We have a lot of research to do.”

ANTIBIOTICS AND WELFARE

The two major issues facing the poultry industry and livestock in general are reducing the use of antibiotics and addressing the changing expectations around animal welfare. “Our big fear here is avian influenza,” says Roberts. “We had one outbreak in British Columbia and they ended up having to recall over a million birds. It’s just incredible what happens when you get something like that.”

The cluster supports research on avian influenza vaccines, with some projects aimed at improving the innate immunity of the birds themselves so they can fight off the sicknesses without the need for as much medication. But it’s a double-edged sword because as well as medication can work, constant and inappropriate exposure has led to the development of antimicrobial resistance. Roberts bristles at the thought of the majority of the blame been apportioned to medicine used in animals. “Most of that comes from human medicine,” says Roberts. “Although it’s easy to throw stones and not look in the mirror.”

Nevertheless, the industry and researchers are realizing that something needed to be done. “Livestock agriculture in general got quite lazy when we figured out if we could just pump the drugs into the animals it took care of a lot of things without us having to worry too much about improved management,” says Roberts. “Now society is looking at it and saying, ‘Woah, woah, there are some downsides here.’”

The downside of resistant bacteria has seen the cluster fund ways of reducing the use of antibiotics and finding alternatives besides vaccines, including new management practices, and the study of epigenetics: why some birds adapt really well and some don’t. This brings home the value of the cluster and the CRPC’s role. About two months ago they had a meeting with the Agriculture Canada on how to cooperate on genomics research. “There are some things that will benefit poultry,” says Roberts, “and what resources Ag Canada has and then we can turn around and talk to the universities about resources you have and match them up. That’s something that we do a lot of; trying to coordinate collaboration not just between government and a university but the universities themselves.” On some projects there can be three and sometimes four different universities working alongside a government researcher. “That wouldn’t happen without the cluster because we’re looking at – at least for poultry – larger and more comprehensive projects with a longer timeframe,” says Roberts.

WORKING TOGETHER

No matter what strand of research, the cluster should find success because of the input of the stakeholders. “[It’s] what industry’s priorities are, what the university researchers’ priorities are and how we make those things come together. Government, I’m not sure what their priorities are,” Roberts chuckles.

The cluster also allows research to be planned for the future. Standard funding is for two to three years, but as many as five. “The ones that go two years, they’ll be out in the industry commercially or adopted by producers before the cluster is done,” he says. “Other ones are a step forward in something that will make another cluster in another five years to bring to fruition. It is management-intensive for us as the recipient but it allows us to really think strategically and longer term. We’re covering everything in the cluster that needs to be researched.”

And the wheel keeps turning.

Canadian Food Business

Canadian Food Business