Joyce Irene Boye*

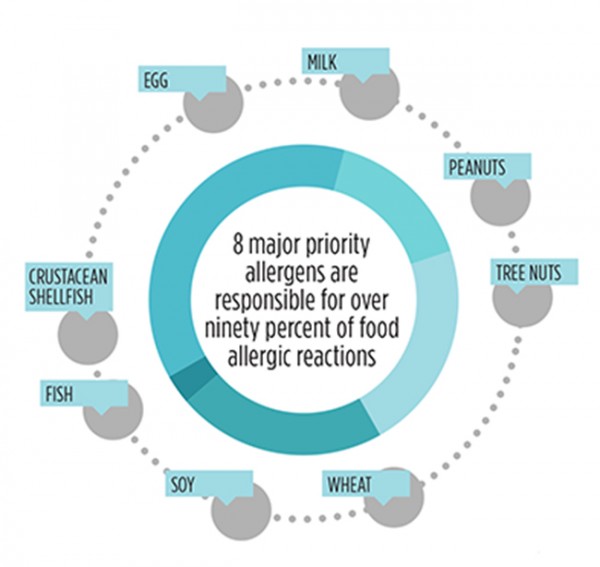

Food hypersensitivity, which includes food allergy and food intolerance, affects many Canadians and is a subject of growing health concern. Approximately 3-4% of adults and 5-6% of children reportedly suffer from food allergy (Samson 2004, 2005; Ben-Shoshan et al., 2010). Although often used interchangeably, food allergy and food intolerance are different types of food reactions. Food intolerance is an adverse food reaction that does not involve the immune system but which may induce an idiosyncratic, metabolic or toxic response to a food (e.g., lactose intolerance). Symptoms can include gastrointestinal distress (e.g., gas, cramps, bloating and pain), heartburn, irritability and headaches. Food allergy, on the other hand, is an immunological reaction resulting from the ingestion, inhalation or atopic contact of a food or additive. Symptoms of food allergy are varied and may include skin rash, hives, swelling of the eyes, face, lips, tongue and throat, itching, migraines, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, cramps, and in some cases anaphylactic shock or death. The eight major priority allergens responsible for over ninety percent of food allergic reactions are milk, egg, peanuts, tree nuts (almonds, Brazil nuts, cashew, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pine nuts, pistachios, walnuts), fish, crustacean shellfish, soy and wheat. In Canada, mustard and sesame are also considered as priority allergens, along with sulphite food additives (e.g., potassium bisulphite, sodium metabisulphite, etc) (www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/securit/allerg/index-eng.php). Although sulphites do not elicit true allergic reactions, the symptoms they provoke in sensitized individuals are very similar to true food allergic reactions.

Gluten sensitive enteropathy (GSE) (commonly referred to as celiac disease) is another abnormal immunological response to gluten/gliadin in genetically susceptible individuals which results in a diseased state frequently characterised by damage of the lining of the gut (i.e., villous atrophy) (Fasano & Catassi, 2001). Whereas symptoms of celiac disease are typically associated with damage of the intestinal tract, symptoms such as diarrhea, anemia, weight loss, vomiting, poor appetite, gas, bone pain, behavioural changes, muscle cramps, fatigue, ulcers and tooth discoloration have been reported. Foods responsible for GSE are gluten containing cereals (i.e, wheat, barley, rye, triticale, spelt and kamut). Research in the last few years suggests that oat is safe for most GSE patients; it is, however, included in the list of gluten containing foods in Canada. Manufacturing practices used in commercial oat production often result in the contamination of oat with other gluten containing grain. Special production practices are required to ensure that oat is free of celiac-provoking gluten proteins. Some oat products labelled as free from these grains are marketed today for celiac patients (e.g., Pure Oats).

Food-dependent exercise induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA) is another form of food allergy induced by exercise. FDEIA is unique in that the food or exercise alone does not provoke an allergic reaction but the combination provokes an allergic response. The precise pathophysiology is poorly understood and symptoms can include urticaria, respiratory and gastrointestinal manifestations, angioedema, hypotension and shock (Horne & Lin, 2008). Various foods have been implicated such as wheat, soy, shellfish and peanuts.

Labelling of food allergens

The prevalence of food hypersensitivity appears to be on the rise (Osterballe et al., 2005). Due to the severity of allergic reactions and the social costs for allergy sufferers many countries have established regulations to protect allergic consumers. In Canada, Health Canada requires that all prepackaged foods containing priority allergens be clearly labelled using commonly used words for these allergens (e.g., “wheat” or “egg”). The allergen may be indicated in the list of ingredients or in a “contains” statement immediately following the list of ingredients. When listed as an ingredient, the common name of the allergen must also be used (e.g., INGREDIENTS: Potatoes, wheat starch, corn oil, salt, seasoning (milk), sulphites). If manufacturers elect to state the allergens in a “contains statement” then they must list all allergens present in the food including sulphites if present at 10 ppm and above (e.g., INGREDIENTS: Potatoes, wheat starch, corn oil, salt, seasoning CONTAINS: milk, wheat, sulphites). Allergens present in wines and spirits and wax coatings must also be declared. The only prepackaged foods exempt from allergen labelling are highly refined oils (except peanut oil). Processing treatment used for highly refined oils removes residual allergen provoking proteins. Unrefined or semi-refined oils may contain the protein fraction of the seeds from which they are derived and so must be avoided by allergy sufferers and companies making food products intended to be free of these allergens. Whenever peanut oil is used, however, Health Canada requires that the source of the oil “peanut”, be always identified. Common names for plant sources of hydrolyzed protein must also be declared on all pre-packaged foods.

Allergen threshold or eliciting dose

The minimal amount of food required to provoke an allergic reaction is described as the threshold dose or eliciting dose. This dose varies significantly between allergy sufferers and is dependent on a variety of factors including the nature of the allergen, the extent to which it is processed, the type of processing it is subjected to and the food matrix at the time of consumption. This makes it very difficult to set an acceptable limit for the presence of allergens in foods. Efforts are underway to develop models from clinical data to allow such limits to be set. A few countries, including Australia and New Zealand, have set threshold limits for some allergenic foods. In Canada, sulphites for example must be labelled when they are present in foods at levels greater than 10 parts per million. Health Canada has also determined that for most people suffering from GSE, a level of 20 ppm provides adequate protection and so foods containing up to 20 ppm may be labelled as gluten free. A similar recommendation has been made by the Codex Alimentarius for gluten-free food labelling. In Canada, Health Canada defines gluten as any gluten protein or any modified gluten protein, including any gluten protein fraction, that is derived from the grains of barley, oats, rye, triticale, wheat, kamut and spelt, or grains of hybridized strains created from these.

Allergen management during processing

Avoiding allergens in the food supply is challenging for the food industry. Successful avoidance requires an understanding of the sources of allergens in the food chain and a good allergen management program. Crops grown in proximity to one another and harvested with the same equipment without appropriate cleaning could introduce allergens during production and primary processing. Ingredients used in food processing, if not properly sourced, could contain undeclared allergens. Lack of appropriate cleaning procedures in between processing of different products could introduce allergens in prepackaged foods. Rework, which involves reusing or reprocessing of unincorporated food product with new products, could introduce allergens into lines intended to be allergen-free. Indeed, waiting until a food is completely processed before testing for allergens may not be the most efficient way to ensure a food is free from allergens. From formulation to the sourcing of ingredients and at every stage of processing, precautionary steps need to be taken to ensure that the introduction of undesired allergens is avoided.

Precautionary labelling

Some food industries have attempted to manage the presence of allergens in their foods by using precautionary labelling (e.g., may contain, or processed in a facility that also produces “X”). Whereas these precautionary statements may be useful, their overuse by food manufacturers has resulted in a decrease in consumer confidence and in some instances disregard of the precautionary statements which puts the health of consumers at risk. Health Canada has recently made revisions to its guidelines for precautionary statements use. While this remains voluntary, Health Canada recommends that the only statement used be “may contain [X]”, where X is the name by which the allergen is commonly known. Precautionary statements should only be used when the inadvertent presence of allergens can’t be avoided. Companies are therefore expected to have made every effort to avoid the presence of allergens whenever this statement is used.

Allergen testing in foods

Depending on how it is used, allergen testing may be used as part of a robust allergen management program. A wide variety of allergen test kits which are capable of detecting allergens at very low ppm levels are available on the market today. For accurate detection of allergens, appropriate test kits must be used (e.g., a food to be tested for the presence of whey protein should be analysed with a kit detecting total milk protein or beta-lactoglobulin and not casein). Processing can influence allergen detection. As a result, some manufacturers have developed kits to address specific challenges with processed foods (e.g., high tannins in chocolate which makes proteins difficult to extract; gluten proteins which require a special extraction buffer; egg which aggregates when cooked and may be difficult to extract). Recent studies by Gomaa et al. (2012) and Gomaa and Boye (2013) reported marked decreases in allergen recovery after cooking of some foods and in some instance false negatives were recorded. A false negative detected by an allergen kit does not, however, indicate that the food is safe. Allergenic epitopes (i.e., parts of the protein that provoke allergic reactions) may be liberated after being hydrolysed by enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract which can result in the provocation of an allergic reaction. The processing method used, including temperature and processing time, as well as product size can significantly affect allergen detection and quantification. The method used for allergen detection, therefore, needs to be carefully selected as it can have an impact on allergen recovery. Using appropriate reference materials, buffers and extraction procedures is necessary to ensure accurate detection of food allergens.

Conclusion

Food allergy will likely continue to be a problem into the foreseeable future. Health Canada has provided regulations to ensure that allergic sufferers are protected. The Canadian food industry must remain vigilante and keep abreast of best practices to allow them to comply with regulations while offering consumers a variety of safe and nutritious foods. In addition to the priority allergens, some fruits, vegetables, pulses may also provoke allergic reaction. While these are not currently regulated, it is important that the food industry be aware of them as there may be opportunity to develop niche food products to capture these markets. The allergen-free food market presents tremendous market opportunity and with the right information and know-how, the Canadian food sector can position itself to take advantage of this growing market.

References

[1] Ben-Shoshan M., Harrington D.W., Soller L., Fragapane J., Joseph L., St Pierre Y., et al. 2010. A population-based study on peanut, tree nut, fish, shellfish, and sesame allergy prevalence in Canada. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 125, 1327-1335.

[2] Fasano, A., Catassi, C. 2001. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: An evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology, 120 (3), 636-651.

[3] Gomaa A., Ribereau S., Boye J. 2012. Detection of allergens in a multiple allergen matrix and study of the impact of thermal processing. Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, S9:001. doi:10.4172/2155-9600.S9-001

[4] Gomaa, A., Boye, J.I. 2013. Impact of thermal processing time and cookie size on the detection of casein, egg, gluten and soy allergens in food. Food Research International, 52(2), 483-489. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2013.01.019 .

[5] Horne, N., Lin, R. 2008. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Internet Journal of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology, 6, 1.

[6] Osterballe, M., Hansen, T. K., Mortz, C. G., Høst, A., Bindslev-Jensen, C. 2005. The prevalence of food hypersensitivity in an unselected population of children and adults. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 16, 567-573.

[7] Sampson H.A. 2004. Update on food allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 113, 805-819.

[8] Sampson H.A. 2005. Food Allergy – accurately identifying clinical reactivity. Allergy, 60, 19-24.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 3600 Casavant Boul West,

Saint Hyacinthe, Quebec, J2S 8E3

(*Corresponding author: E-mail: joyce.boye@agr.gc.ca)

Canadian Food Business

Canadian Food Business